Transportation, Health Equity and Social Justice in Regional Transportation Planning

What can fine-scale spatial modeling of health impacts from long-range transportation plans do to support racial and social justice? More than you may realize, according to CAPLA’s Nicole Iroz-Elardo, assistant research professor of planning.

By Nicole Iroz-Elardo PhD

Regional transportation plans (RTPs) may seem wonky to some, but Nicole Iroz-Elardo, assistant research professor of planning in the College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture at the University of Arizona, sees them as critical for articulating and implementing a region’s transportation, housing and environmental goals. In this CAPLA Thought Leadership piece, she shares how including a spatial analysis of health in the 2018 RTP of San Joaquin Council of Governments (Stockton, California) provides an innovative, successful example.

Required by federal law as a condition of federal transportation funds, regional transportation plans (RTPs) with 20- to 30-year horizons are updated every four or five years, depending on a region’s emission-related air quality performance. RTPs must show how planned growth will meet federal air quality, environmental justice and non-discrimination requirements. RTPs lean heavily on modeling current transportation patterns at the household level and small “transportation analysis zones” in order to predict the patterns of travel and emissions 20 years into the future. All other transportation plans and investments have to be consistent with the RTP—so as a planning instrument, it really sets the tone for all other land use and transportation decisions in a region.

California, in its commitment to curb greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change, leads the way in aggressive methods innovation for RTPs, including adding health as a prominent co-benefit. Even though there are over two decades of high-quality evidence showing walkable places increase physical activity and health, this co-benefit of good planning is typically mentioned but not modeled. Quantified health benefits that are broken down below the regional level are even less common. Without this level of detail, there is little way to understand the health equity implications by neighborhood, income and race even though cities are known for their uneven distribution of disease.

Places like Los Angeles are committed to changing this, investing in making health outcomes explicit in their regional RTPs. As an expert in the public health implications of land use and transportation changes, I spend a lot of time in development of practitioner tools. I have supported several states and regions, including Los Angeles, through novel applications of quantifying health impacts over the past five years.

In the September 2020 issue of Social Science and Medicine, I worked with Jessica Schoner, Eric H. Fox and Lawrence D. Frank ‘85 BLA of Urban Design 4 Health and Allen Brookes of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to report on a novel application of the National Public Health Impact Model (NPHAM), funded by the EPA and developed at Urban Design 4 Health. This particular analysis shows the promise of health equity modeling to support socially just transportation decisions.

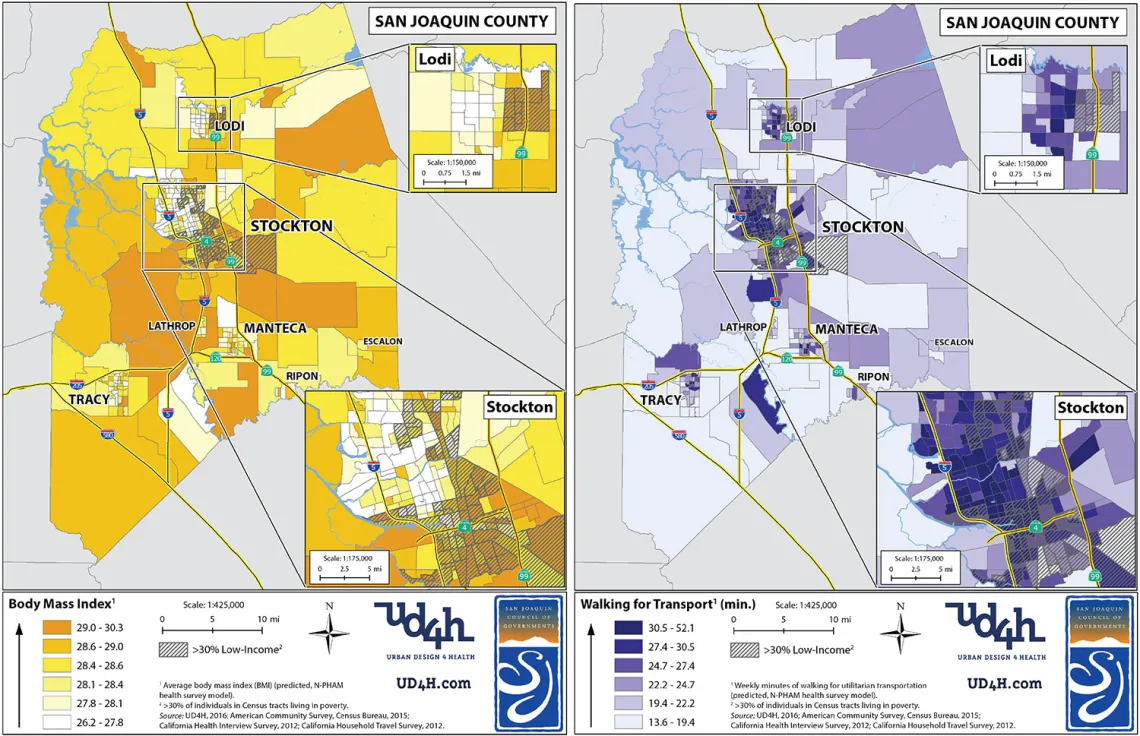

Set in San Joaquin County (Stockton), California, the analysis provides estimates of physical activity from walking for leisure and transportation as well as changes to body mass index for both the current and horizon years of the SJCOG 2018 RTP. Because NPHAM was developed to model at the Census Block Group level—roughly the size of your immediate neighborhood—these public health metrics can then be analyzed for spatial equity, including analyzing how neighborhoods with high concentrations of low-income and/or racial minority households are performing compared to their less vulnerable neighbors.

Choropleth maps showing the Census block group level geographic distribution of predicted body mass index and weekly minutes of walking for transportation highlighting low-income areas across San Joaquin County.

The results of the analyses are not overly surprising for someone who works in this field. The modest increases in physical activity and decreases in body mass index are pretty typical in areas that become more dense, have more nearby destinations to walk to and more public transportation. It isn’t much, but a little bit here and there adds up to better population health. For example, the fine spatial public health analyses showed that the projected change in increased minutes spent walking for transportation is three times larger in neighborhoods in which high concentrations of minorities or low-income households reside when compared to whiter and higher-income counterparts. Still, this increase is not enough to bring minority and low-income neighborhoods up to parity in the horizon year—a finding that deserves discussion.

When we started comparing different definitions of a “community of concern”—a name California gives to neighborhoods of concentrated poverty or racial minorities—even more interesting patterns started to appear. RTPs typically use a lowest quartile (25 percent) of concentrated poverty or racial minority as the threshold. California, in an effort to standardize metrics and prioritize funding in areas with the most need, uses an “Environmental Justice Index” which captures both low income and race, normalized across the state. Because Stockton is less wealthy than its Bay Area or Southern California neighbors, approximately 40 percent of the block groups in San Joaquin County are Environmental Justice areas. This more generous definition appeared to be performing much better than the more restrictive lowest quartile approach, implying that the modestly working class neighborhoods were benefiting the most.

I approached the planners and asked if this pattern reflected the policy goals of the regional government. They also found it interesting, but confirmed there was not an explicit goal to focus investments on moderately low-income or moderately diverse neighborhoods. While such a goal might be justifiable in some communities, this analysis highlights how much we guess when putting together long-term policy and investment strategies to meet equity goals.

Until we know what the likely consequences are—including the expected spatial impacts of region-wide investments—it is difficult to fine-tune investment strategies to support health equity and racial justice in minority and low-income neighborhoods. For example, regional or local transportation governments could use discretionary monies to bolster larger-scale projects that improve walking for transportation by creating additional safe and inviting public spaces, improving local parks to have more appealing walking paths and adding culturally relevant programming to also increase walking for leisure, which is typically lower for low-income and minority groups.

I firmly believe that planning tends to overly emphasize models and instead favor a mix of quantitative and qualitative approaches to understanding the health impacts of the built environment and that make room for community voices. Yet modeling has its place and will continue to be the basis of many regulatory transportation decisions well into the future. Improving the modeling itself to explicitly answer questions about race and class is needed to further racial justice. For example, we desperately need a way to accurately predict where communities of concern will be in 20 to 30 years to make our models more accurate and avoid or mitigate gentrification. Anything that improves fine-scale spatial improvements of community centered co-benefits is likely to help bolster social justice.

In the meantime, I will continue to develop tools to explicitly incorporate health, racial and social justice analyses into transportation plans and advise regional and local governments about how to align their professed values with their investment and policy strategies.