The Architectural Laboratory of Frank Lloyd Wright

CAPLA Thought Leadership

Frank Lloyd Wright's Oak Park studio. Photo by James Caulfield.

By Lisa Schrenk PhD, Associate Professor of Architectural History

Lisa Schrenk, Associate Professor of Architectural History.

Standing in the doorway under the large triangular gable of his home, a young boy with long curly hair clung tightly to his mother’s hand. He wondered why she was in tears when his father in front of them was smiling as he waved goodbye. It was years later that the boy, Frank Lloyd Wright’s youngest son Robert Llewellyn, understood what had taken place during the only “small child memory” he had of his father. The architect was turning his back on his Oak Park home and studio, a site where he had previously found tremendous fertile growth in both his personal and professional lives.

In happier times, Frank Lloyd Wright’s suburban studio, connected to the boy’s quaint, shingle-style home by an unheated corridor, served as one of the most important sites in the development of modern architecture in the United States. The unusual-looking brick and shingle structure, at the intersection of a major artery into Chicago and one of Oak Park’s most desirable residential streets, included a large two-story drafting room attached to an octagonal-shaped library by a reception hall with a business office in the rear. Wright decorated the interior spaces with native plants and other inspirational elements, from reproductions of classical sculptures to Japanese prints to his own furnishings and drawings. Within the walls of this unconventional workplace the architect incorporated exploratory practices introduced to him as a youth and lessons learned in the offices of early employers and from progressive colleagues into a personal design ideology appropriate to the rapidly changing cultural and societal conditions of an industrializing world. It was during the years he operated his Oak Park studio (between 1898 and 1909) that Wright achieved broad recognition as a leading American architect.

As a young designer sensitive to his environment, Wright strove to place himself in a setting that allowed him to continue the type of firsthand explorations of the world he had experienced as a child among the rolling hills of south central Wisconsin. This desire contributed to his flight from a series of professional settings early in his adult life—from the classrooms at the University of Wisconsin, from the architectural offices of his early employers and Steinway Hall colleagues in Chicago, and even from the peaceful tranquility of his own suburban home studio—eventually to return to Spring Green, Wisconsin, and the rural, familial landscape of his childhood.

1899 photo of Frank Lloyd Wright's Oak Park Studio. Image courtesy Lisa Schrenk.

The unusual office Wright built immediately north of his Oak Park home in 1897–98 formed the most significant stop on this developmental peregrination. The domestic environment of the home studio and its suburban surroundings offered a more integrated, organic setting for the production of his predominantly residential projects than would a downtown architectural office. It additionally presented a more feminized environment, making the studio a comfortable place for women, both as employees and as clients, in an era of a growing public female voice in the United States.1 The presence of strong women and the close proximity to the architect’s home and family played major roles in shaping the office.

Free of institutional constraints, Wright produced a personal work environment that served as a central site in the rise of a new modern form of architecture and in the furthering of design principles that came to define his work throughout a long and productive career. This advancement took place within a carefully conceived yet continually evolving setting. While design education in the United States was moving away from the tradition of training through apprenticeship to structured educational programs at universities, colleges, and technical schools, Wright fashioned his studio more like a French atelier or an English Arts and Crafts workshop, allowing for hands-on educational experiences.2 Particularly during the early years, spirited dialogues and debates filled the office as it presented a vibrant learning environment for not only Wright but also the small community of designers working for him. The deep personal significance of the Oak Park home studio for the architect is, in part, reflected in the fact that he designed changes for the property even after his departure, including a major alteration of the studio in 1911, less dramatic modifications in the later 1910s and 1920s, and additional remodelings as late as 1956, just three years before his death.3

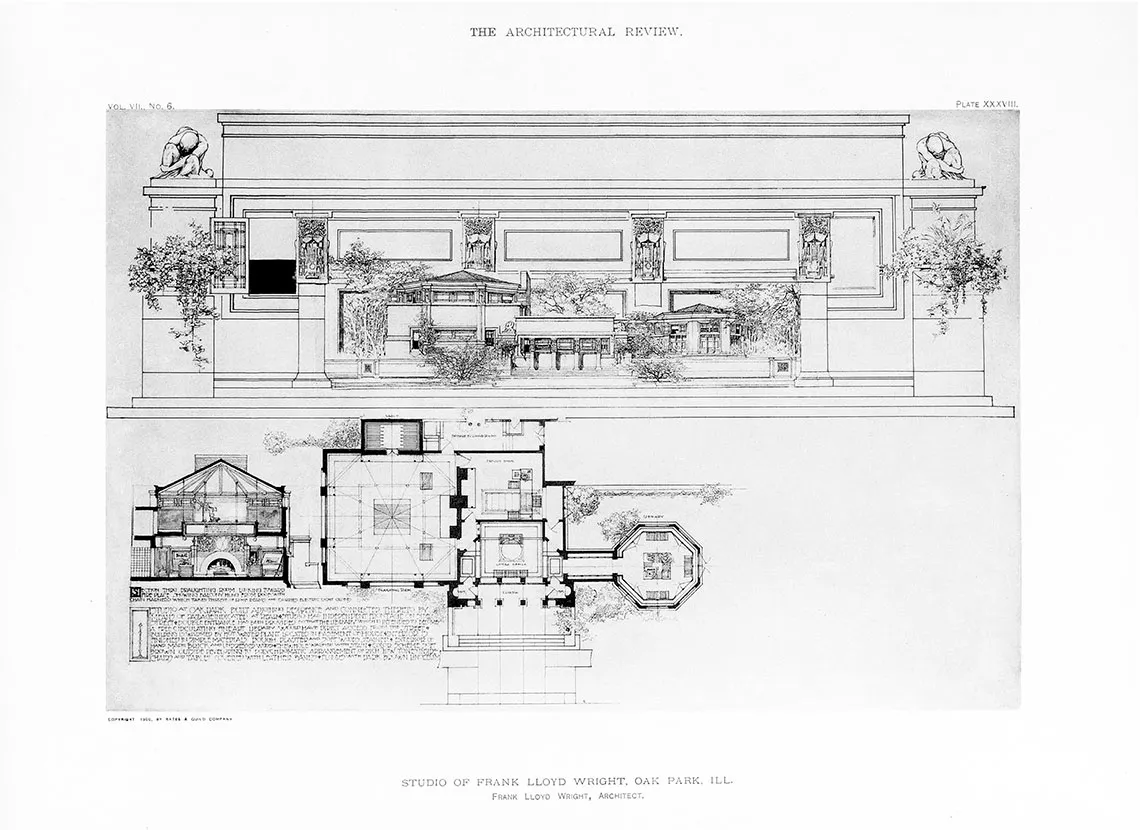

Architectural drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright's Oak Park Studio appearing in the June 1900 issue of The Architectural Review. Image courtesy Lisa Schrenk.

The Home and Studio Building

Only 18 years after his last design changes for the building, the architect’s suburban home and studio complex was deemed “architecturally confusing having lost the thrust of Wright’s original inspiration.”4 Divided into six separate apartments, the building had deteriorated significantly and was filled with “green shag carpets, water-damaged walls, and uneven floors.”5 One note from the 1960s read, “There were layers of paint on the beautiful woods, the window frames in his former drafting room were painted a garish red, some of the walls had flowered wallpaper on them.”6 Wright’s son Lloyd was greatly dismayed that “so little of his childhood home remained visible through its various ‘modernizations.’”7

Rumors of the building’s imminent dismantling emerged, some of which speculated that its art glass windows were going to a museum in France and the home’s magnificent playroom to a sheik.8 At the time these stories seemed plausible, as a not very different fate had just befallen the Deephaven, Minnesota, residence Wright designed for Francis Little: its living room shipped off to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, a hallway to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, and the library to the Allentown Art Museum in Pennsylvania.9 The reports of the demise of Wright’s home and studio galvanized community leaders to save the building. After two years of negotiations, a consortium of local banks under the name of the Oak Park Development Corporation bought the property in May 1974.10 In the same year, the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Foundation was established to acquire, restore, and open the site for public tours.11 The foundation transferred ownership of the property to the National Trust for Historic Preservation under an innovative co-stewardship arrangement with the trust leasing the site to the foundation, which was tasked with restoring and operating the building as a museum.12

Fireplace in the Oak Park's Studio's drafting room. Photo taken in 1899. Image courtesy Lisa Schrenk.

At the time, the site’s historical significance was evident in the fact that in 1972 it became one of the first properties to meet all criteria for listing on the National Register of Historic Places: (1) it was associated with “events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history” (the rise of a new form of modern American architecture known as the prairie house); (2) it was associated with “an event that significantly contributed to American history” (the early career of Frank Lloyd Wright); (3) it embodied “the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction” or represented the work of a master or possessed high artistic values (both the residence and studio were important projects in Wright’s oeuvre); and (4) it yielded “information important in history” (the complex provides great insight into Wright’s early career).13 In 1975 the building became a National Historic Landmark, and the foundation launched a meticulous, volunteer-led restoration. Their aim was to bring the building back to its physical state in 1909, the last year Wright resided there.

I was hired as education director for the foundation near the end of the building’s restoration phase to help make both the museum and the knowledge uncovered during the process more accessible to the public. Unfortunately, the physical restoration does not reveal the tremendous interactions between Wright and his employees and clients or other experiences and events relating to the studio, including the creation of some of the most remarkable works of modern American architecture. Neither does it fully address the relationship of Wright’s home and family next door to his work environment. Furthermore, it does not disclose the dramatic evolution of the building over time, not only in the years that Wright worked and lived there but throughout its life. The book The Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright offers insight into these formidable stories.

Reprinted with permission from The Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright, by Lisa D. Schrenk, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2020. All rights reserved.

Schrenk, who joined CAPLA in 2012, is a leading authority on the architecture of international expositions and the early work of Frank Lloyd Wright. She has also presented papers and authored publications on Art Deco art and architecture, Radio Flyer wagons, plan-book architecture and thin-shell concrete. Her books include Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of Chicago’s 1933-34 World’s Fair and The Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright. She shares both her firsthand experiences and photographs from her extensive travels with students in her history/theory courses, with the public via her image blog AdventuresinArchitecture and with colleagues through SAHARA, a digital-image database sponsored by the Society of Architectural Historians. Schrenk initiated the University of Arizona's Women in Architecture Society and is currently involved in the creation of the global, interdisciplinary Institute for the Study of International Expositions (ISIE). Since 2015 she has worked with CAPLA students and others to assist with the State of Minnesota's bid efforts to host Expo 2027, the first world's fair in the United States in over 40 years.

End Notes

- For more on the feminine, nurturing environment of the studio, see David Van Zanten, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Kindergarten: Professional Practice and Sexual Roles,” in Architecture: A Place for Women, ed. Ellen Perry Berkeley (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989), 55–61, and reprinted in Not at Home: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture, ed. Christopher Reed (London: Thames and Hudson, 1996), 92–97.

- In January 1887 it was reported in the Chicago periodical Building Budget that the “old-fashion system of apprenticeship was at an end; that it was opposed to the genius of our institutions . . . and not generally sustained by the laws of the different States; and that a return to it was not really practicable.” Building Budget 3 (January 1887): 1–2.

- The property title during the years Wright owned the home and studio was almost always tied up in deeds of trust and lawsuits. See appendix F.

- Ann Abernathy, “Outline: Restoration Alternatives, Goals, Procedures,” August 1985, 1, FLWHSRC.

- Ann Mahron, past president of the organization, in Wes Venteicher, “Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Celebrating 40 Years of Tours,” Oak Leaves, 15 July 2014. Alvin Nagelberg, “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Former Home at 951 Chicago Av. in Oak Park Up for Sale,” Chicago Tribune, 5 October 1972.

- A copy of the photograph is in the collection of the FLWHSRC.

- Eric Lloyd Wright, foreword to Zarine Weil, ed. Building a Legacy: The Restoration of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park Home and Studio (San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2001), vi.

- The owner’s son also threatened to sell some of the art glass. Don Kalec to author, 30 August 2016.

- The dismantling took place in 1972.

- The property was purchased for $168,000 from Clyde and Charlotte Nooker, who had acquired it in 1946. Weil, Building a Legacy, 17.

- The foundation was renamed the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust in December 2013.

- “Trust Acquires Wright Home,” Preservation News 15 (October 1975): 1; Bob Trezevant, “Laying the Foundation for Historic Preservation: A Timeline, 1946–Present,” Wednesday Journal, 25 November 2014, available at http:// www .oakpark .com /News /Articles /11 -25 - 2014 /Laying - the -foundation -for -historic -preservation/; Nagelberg, “Former Home.” The organization purchased back the building in May 2012. On the restoration, see Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio Foundation, The Plan for Restoration and Adaptive Use of the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), hereafter Plan for Restoration, and Weil, Building a Legacy.

- U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Interagency Resources Division, “Guidelines for Evaluating and Documenting Traditional Cultural Properties,” National Register Bulletin 38 (1985): 11–12.