The Transformative Career of a Lifelong Explorer: R. Brooks Jeffery ’83 B.Arch, Professor Emeritus of Architecture

Though Emeritus Professor of Architecture R. Brooks Jeffery retired from the University of Arizona in June 2022 as associate vice president for research, at CAPLA he will be long acclaimed for his dedicated work across many roles, including associate dean and Drachman Institute director—as well for his wide-reaching service and award-winning research on heritage conservation in arid environments.

Learn more about Brooks in our interview, which was held over the summer and fall:

What sparked your initial passion for heritage conservation?

I was born in Janesville, Wisconsin, just south of Madison. One of my profound memories was being dragged by my mother to the local historical society where she volunteered. There, she was given the project of reviewing historic photographs of Janesville’s 19th century buildings and driving around to locate their current address. Of course, many had been modified so it became an investigative exercise in identifying various architectural features between the historic photographs and current conditions. It was a great education, whether I realized it at the time, and began a life-long passion for historic built environments.

Early in your career you served as preservation project manager in the Republic of Yemen. Tell us a little about that experience, and how that informed your lifelong work in heritage conversation.

R. Brooks Jeffery in Yemen, 1986.

After graduating from the University of Arizona’s College of Architecture (now CAPLA), I began working in an architectural firm in San Diego—but after about three years, I got an itch for travel and adventure. As an architecture student of the 1970 and 1980s, I was drawn to the college’s faculty whose research and community outreach activities focused on energy conservation, traditional architecture of arid regions and the preservation of Tucson original neighborhoods. In many of these areas, the college’s faculty were national scholars and community leaders. This mosaic of influences guided my path to join the Peace Corps, where I cared less about what I was asked to do as a volunteer as long as it took me to a region where I could explore the vernacular architecture of desert regions of the world.

This led me to Yemen, an extremely isolated country in the Arabian Peninsula renowned for its vernacular earthen buildings unspoiled by European (and other colonial) architectural influences. I was there for three years. I started as a project manager supervising water infrastructure projects in rural villages, then moved to the capital city, San’a, where I taught English as a second language at the national university. There, I was introduced to a team of UNESCO experts who were working with governmental and non-governmental organizations to mobilize efforts on the newly designated World Heritage Site of San’a’s old walled city: a magical, dense landscape of tower houses of earthen construction (up to 10 stories tall) and secluded communal gardens.

I was fortunate that the Peace Corps not only allowed me to be reassigned to this project (requiring me to extend my volunteer status for an additional year) but agreed to recruit a new cohort of volunteers that I then trained to work with me on the UNESCO campaign. In partnership with UNESCO and other international entities, our team advocated for international embassies to relocate to the Old City and fund the restoration of their buildings, created localized conservation guidelines based on international standards, developed training programs for local artisans to resurrect traditional building crafts that had been lost, and developed public awareness campaigns to recognize and protect the country’s unique architectural heritage. It was a transformative experience on multiple levels and was a convergence of both my passion and skill sets that launched a career path on which I’m still an explorer.

Earning a Master of Information Science following your Bachelor of Architecture wouldn’t seem to be the most obvious graduate degree. Why did you choose that degree, and how has it helped you in your career?

While in Yemen, I remained in contact with a number of people in the College of Architecture, including Kathryn Wayne, the architectural librarian for whom I’d worked as a student (I need to note here that the college had its own library until the 1990s) and became an early mentor in my career. As I was contemplating a post-Peace Corps career path, she reached out with a job offer as a library assistant, which I saw as an ideal initial landing place where I could get my bearings and contemplate next steps. It was great to be in an academic setting and re-engage with my faculty mentors, and she encouraged me to pursue a master’s degree while working in the library (basically tuition-free). She encouraged me to embrace the librarian-scholar career path and focus my immediate efforts on the (then-dormant) Arizona Architectural Archives, a collection of architectural drawings and other materials representing Southern Arizona’s iconic architects: Annie Graham Rockfellow, Roy Place, Josias Joesler and William Wilde, among others. This was also during a paradigm shift for academic libraries, which were transforming from being stodgy repositories of books to vibrant resource centers focused on digital access to intellectual content as part of the emerging “information age” movement (remember, this was the 1980s). Even the UArizona master’s program changed its name from Library Science to Information Science to reflect this shift in brand image (the program has since changed its name to Library and Information Science). It was a great education and like many master’s-level programs, it taught me how to be a scholar, and I was privileged to have an ideal laboratory and community in the college in which I could pursue a scholarly direction in my career.

When did you join CAPLA, and in what role?

I’m in the unique position of having occupied multiple roles and statuses during my 35 years at CAPLA—classified staff, continuing status academic professional, tenured professor and administrator. I joined the College of Architecture in 1988 as a library assistant staff position, then was put on a continuing status track (tenure-like status for academic professionals) as an assistant curator, where I oversaw the college’s slide collection and an online visual database (way before Google Images…), and the Arizona Architectural Archives where I began publishing articles and other scholarship on local architecture. Being on continuing status track also allowed me the opportunity to both teach and serve on master’s thesis committees. There was a recognized need for more rigor in the architecture graduate program and I was asked to create and then began teaching a course on architectural research methods for graduate students. This teaching experience grew to include a series of seminar courses and Professor Bob Giebner’s preservation classes after he passed away in 1994.

In 1997, Richard Eribes was appointed dean and came to the college with a vision to expand the then one-department college, which he saw as a threat to be absorbed by another larger college during a belt-tightening time at the university when such consolidations were commonplace. He successfully administered the transfer of the Planning and Landscape Architecture graduate programs into a multi-unit college, now CAPLA, and in 2004, asked me to serve as associate dean. My initial role as an administrator was to coordinate the physical, operational and research integration of the three academic departments, plus the Drachman Institute, while he lobbied for funding to remodel the existing college and build an addition, the CAPLA East Building, which was completed under Dean Eribes’s successor, Chuck Albanese, in 2006.

During Dean Albanese’s three-year tenure, my associate dean portfolio expanded to include building construction administration and coordinating college strategic planning efforts in preparation for recruiting our next dean, Jan Cervelli. I continued serving as associate dean under Dean Cervelli for one year, when I was offered the position of Drachman Institute director in 2009, where I served until 2016.

The CAPLA East Building, viewed from the Underwood Sonoran Garden, the year following completion. Photo by Bill Timmerman.

What did you find most rewarding about your work at CAPLA?

The most rewarding by far is helping students realize their potential as future citizens and leaders, while preparing them for practice as emerging professionals. I’ve been privileged in my positions at CAPLA to engage with students in the classroom, conducting research and in community outreach projects where we embraced a service-learning mode that made students active learners while addressing real-world problems.

Equally rewarding has been the funded research and scholarship I’ve produced that stands on the shoulders of my CAPLA mentors—Gordon Heck, Bob Giebner, Kirby Lockard and Ken Clark—that contributes to the body of knowledge of built environments. I’m proud to have carried on my predecessors’ efforts to illuminate under-represented themes such as vernacular built environments, sustainable design in arid climates and elevating the under-recognized significance of local architecture, including the role of women architects and Tucson’s modern architectural legacy.

I’ve also been deeply rewarded by my role as a mentor, both formally and informally, to students and colleagues throughout my career, including most recently as a university research administrator. In this, I’m paying forward the mentoring I received from others, including Dean Eribes and Ron Stoltz, then director of the School of Landscape Architecture, who was one of the best educators I’ve ever known and provided me a master class in academic leadership.

When at CAPLA you worked closely with architecture students and developed lasting bonds with many of them (I’m thinking of Rich Michal, who CAPLA profiled in 2021, for example). Tell us about those experiences—the importance of working with students to help them mature into their careers, and to help you as a faculty member.

When I was a student, many of the faculty would invite students to their houses for parties and dinners with members of the local architectural community, and it wasn’t until later that I realized this was not the norm in academic settings. Beyond the conviviality, the faculty were practicing the truism that relationships are the cornerstone of being a successful professional (and human being…). I’ve tried to carry that ethic forward by breaking down the barriers of faculty-student relationships and embracing students as colleagues where my role was more as a facilitator-mentor. This was particularly important when I was CAPLA associate dean, when we needed to break down the perceptual barriers and stereotypes defined by our individual disciplines. Tapping into my own student experience and recognizing that students are often more open to building interdisciplinary bridges than many faculty, I began inviting the entire CAPLA graduate student body and faculty to my house for an annual orientation party. These community-building experiences were incredibly valuable at the time, and I still get messages from students who reference these events as they are now building their own interdisciplinary communities of practice. In the end, it really is all about relationships.

What advice do you have for students interested in design and/or heritage conservation as an academic pursuit and as a career?

My advice to students is: Heritage conservation has evolved from “historic preservation” (i.e., preserving history) to being part of an integrated toolkit approach to addressing everything from climate change to economic development. When we developed the Heritage Conservation Program, we defined its educational purpose as the “conservation of the built environment as part of a comprehensive ethic of environmental, cultural and economic sustainability.” It is inherently interdisciplinary and provides multiple career opportunities from historical scholarship (making sense of place), sustainable design and community development (place-making) to technical building pathologies and restoration, lab-based materials analysis and public policy-making. The other fundamental tenet of heritage conservation we embrace is stewardship—the sustainable management of resources on behalf of future generations—that connects us to a community and its intangible sense of place. Without it, we’ve lost the cultural identity that defines us as a community, and by extension, as individuals.

What is most urgent in heritage conversation and sustainable design today?

I think the most urgent issue today is the lack of representation in what we, as a society, have defined as being historically significant, and inherited from previous generations as cultural heritage. This is exemplified in the recent removal of confederate monuments and challenging the white-washed version of historical narratives embodied in the buildings, landscapes and artifacts that represent our collective past, i.e., our heritage. There’s a critical need to recognize BIPOC, LGBTQ and other under-represented historical narratives and their associated built environments that broaden our understanding of who we are as a community and nation.

Tell us about your time directing the Drachman Institute, as well as your hopes for the relaunched Drachman Institute.

I was very honored to be appointed Drachman Institute director following Corky Poster’s retirement in 2009. As the college’s research-based outreach arm, Drachman Institute embodies Ernest Boyer’s “scholarship of engagement” by advancing community engagement as a cornerstone of professional design education. For me, this was the perfect intersection of my interests and cumulative experience: collaborative service-learning pedagogy, funded interdisciplinary research projects and impactful engagement with local communities, all within a collective organizational structure of dedicated students, professional staff and faculty.

I was so pleased to see Courtney Crosson appointed as Drachman Institute director after such a long absence of activity. She has the leadership skills, research bona fides and ethic of community engagement required to define the next chapter of Drachman Institute and do it in her own image, just as each of the prior directors have done. The Drachman Institute is in great hands.

What prompted your move from CAPLA to the UArizona Office for Research, Innovation and Impact?

The biggest challenge during my seven-year tenure as Drachman Institute director was the incremental reduction of state funding to our college and the disproportionate burden absorbed by the Drachman Institute. These budget cuts culminated with the complete elimination of state support for the Drachman Institute in 2015 by Dean Cervelli. This required the Drachman Institute to become a financially self-sustaining unit and operate more like a nonprofit than an integrated unit of the college, which was incredibly stressful on the professional staff and me as director. This downsizing in CAPLA coincided with the arrival of a new senior vice president for research at the University of Arizona, Kimberly Espy, who was expanding her team in the UArizona Office for Research and Development (now Research, Innovation and Impact, or RII) to advance research in the arts, humanities and social sciences across the university, which also included oversight of select museums, centers and institutes that report to that office. She invited me to apply and interview for this new university-level leadership position, which I did, and was appointed associate vice president for research in 2016.

Tell us more about the associate vice president for research role itself.

My six-year tenure at RII was divided into two chapters, each with a distinctive role and portfolio of duties. When I first arrived, I was charged broadly with advancing research in the arts, humanities and social sciences across the university. While this was my strategic charge, I also had operational oversight of the university museums (such as the Center for Creative Photography, Arizona State [anthropology] Museum and Museum of Art) and select university-wide research centers (including Confluencenter for Creative Inquiry, Institute for LGBT Studies and Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy) that report to RII.

Admittedly, I found it strange that these world-class arts and cultural institutions were under the auspices of the university research office but felt fortunate that I had the opportunity to be their chief administrator and advocate. While much of the focus was how to increase external research revenue to the university—a primary metric of a Research I institution like UArizona—this new position’s broad portfolio of units also provided an opportunity to re-envision how to elevate recognition of the non-revenue impacts and value of arts and cultural institutions to the university, community and state, consistent with our mission as a land grant institution. This holistic re-envisioning process dovetailed perfectly with the emerging year-long university strategic planning efforts President Robert C. Robbins initiated on his arrival to campus in 2017. As co-lead for one of the strategic plan’s “pillars,” Arizona Advantage: Driving Social, Cultural and Economic Impact, I’m proud of our work to champion a vision for, and codify a set of initiatives that drove strategic financial investments in, UArizona arts and culture that are still being implemented today. Beyond additional funding for programs and facilities, this effort included the establishment of a vice president for the arts position (that reports directly to the president) and an Arizona Arts organizational structure that ensures a unified approach to drive their future efforts.

The second chapter of my tenure at RII was marked by a change in its leadership, under Betsy Cantwell, and a dramatic shift from advocating for arts and culture to overseeing and expanding campus research infrastructure capacity, including university core facilities, lab space optimization, new construction projects and future capital planning. During this period, RII was the “client” for four concurrent construction projects—totaling $189 million—for which I acted as client representative to the design-build teams involved in everything from user group coordination and design development to construction management and building commissioning. Each of these buildings had their own unique contribution to the larger UArizona research enterprise from state-of-the-art facilities for space sciences (Applied Research Building) and transdisciplinary innovation collaboratives (Grand Challenges Research Building) to the university’s first research-focused public-private partnership project (The Refinery at The Bridges). In addition to this operational oversight responsibility, I also spearheaded the development and adoption of a campus-wide research infrastructure strategic plan that provides a roadmap to guide future strategic research infrastructure investments, ensures research resilience through optimal space utilization and expands UArizona research capacity over the next 10 years.

The rising Grand Challenges Research Building is designed to draw on the University of Arizona's core strengths by supporting the expansion of the Optical Sciences, and provide research capacity for the new Center for Quantum Networks. Image courtesy UArizona RII.

What did you find most rewarding about you work with RII?

One of the most rewarding facets of working at RII was the privilege of working with some of the most talented and dedicated people at all levels of the organization doing both the recognized and unrecognized work that enables the university to achieve its many successes. In truth, working at RII was the most challenging job I’ve ever had at the university. It was defined by a series of learning curves on themes of upper university administration that were never part of my world at CAPLA. Chief among these were the vastness of the university research enterprise (a true business with $700+ million of annual expenditures) and its impact on regional economic development, the Arizona Board of Regents’ tri-university performance metrics and how that drives university funding models, the unique challenges of managing world-class arts and cultural institutions, the university-level strategic planning process (one facilitated by McKinsey that involved dozens of stakeholder meetings, vision charters, business cases, and implementation plans) and the university capital planning process to fund new buildings and research infrastructure on campus.

Admittedly, I often felt overwhelmed by the sheer scale and scope of the portfolio assigned to me, but what was the most rewarding was the recognition of how much my architectural education and previous experience in CAPLA was the wellspring to address and resolve highly complex problems and influence decision-making at the highest levels of the university. I'm proud to have represented CAPLA at this level of university leadership and I discovered that empathy, the first principle of design thinking, was my secret weapon during these steep learning curves, especially as I often found myself the lone humanist in a room full of rocket scientists (literally…).

Working at RII, I also became increasingly convinced that we need more people with design education in positions of leadership, both inside and outside the university, where there is great opportunity to make impactful contributions.

You’ve received many illustrious awards, from the Excellence in Resource Stewardship Award from the National Park Service to a number of Historic Preservation Awards from the Tucson-Pima County Historical Commission to the Governor’s Heritage Preservation Honor Award and, just this fall, a Governor’s Heritage Honor Preservation Lifetime Achievement Award. Is there a particular award, or award-winning project, that is especially meaningful, or that represents a particularly compelling perspective?

I’m most proud of the awards that recognized the service-learning model of the Heritage Conservation Program. These were course projects that provided a laboratory for students to learn professional skills, leave the classroom and work in the community where they engaged with the people directly impacted by their work, and then to be recognized by external entities for their contributions to the community. It just doesn’t get any better than that.

You served as a faculty mentor at CAPLA, and perhaps more informally a mentor to academic administrators and others when at RII. Talk to us about the importance of mentoring in an academic institution.

The academy is a wonderful, but mysterious, place. Mentoring is vital to the wellbeing and professional growth of faculty and staff at all levels, from navigating the complexities of a university bureaucracy and defining a professional career trajectory, to providing a leadership pipeline to serve a department, college or university. I’ve been blessed with incredible mentors in my career, and it has always been important to me to pay that forward by mentoring others.

Good mentoring, however, requires meaningful engagement with your mentees and a commitment to balancing the greater good of the institution and ensuring the success of others with your own personal advancement. This isn’t always easy but is the core definition of being a servant-leader. Finding good mentors, especially at an organization as large as the University of Arizona, is the most challenging part, particularly if there isn’t a formal program that reinforces mentoring as both a core value and a duty. As faculty and staff in most colleges tend to remain in their own bubble without engaging with the larger university, I always encourage everyone to perform service at the university level, or even in community and professional organizations, where you will meet people outside your bubble, gain a broader perspective and be exposed to diverse role models with whom you may identify and develop a rich mentoring relationship.

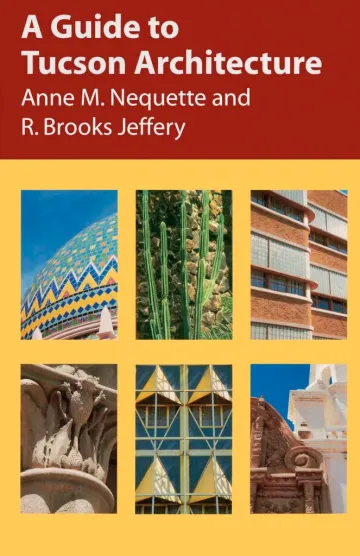

Your books are fascinating—Yemen: A Culture of Builders (1989), A Guide to Tucson Architecture (2002) and Cross-Cultural Vernacular Landscapes of Southern Arizona (2005), to name the first three. Can you choose one of these to tell us a bit about the experience of writing a book and servings as a researcher (and therefore author) in your career in general?

An academic mentor once told me, if your research isn’t published it has no value, which I came to understand as true because our role as a research university is to create and advance knowledge. However, unlike researchers in the sciences where there are multiple venues for publishing research, there are limited platforms for the dissemination of research in the design disciplines. I was very fortunate that at the time when Annie Nequette and I proposed the book idea of A Guide to Tucson Architecture, the University of Arizona Press was very supportive of publishing UArizona faculty and on subjects of more regional scope. Writing and publishing a book, journal article or even other media requires a high level of discipline and a certain level of humility when your work must be scrutinized at various levels, including by the audience that reads it and publicly criticizes it (not unlike design!). After you’ve got that first work published and under your belt, the process becomes much easier both because you’ve established a credibility as a published author and you’ve gained confidence in understanding the relevancy of the body of knowledge you’re attempting to validate through the peer review process. I have also been an advocate for recognizing that this body of knowledge can be advanced through a variety of communications media, including traditional peer-reviewed books, journals, conference presentations and publications, but also through popular media—newspaper articles, a conference field guide (Cross-Cultural Vernacular Landscapes of Southern Arizona), home magazines, television features and websites—which results in the blurring of lines between traditional forms of scholarly dissemination and those that create the greatest impact to the broadest audiences.

Of the many landscapes and cultures you’ve visited in your career, what have you found most fascinating, and why?

Ha! That’s like asking which of my children is my favorite! If I had to pick one, however, it would be Yemen, where I spent three years as a Peace Corps volunteer. Living in a culture where there are very few known references—Arabic language, Islamic religion, non-aligned geopolitics—requires your American worldview to be completely shaken up and teaches you the values of humility and tolerance associated with being a world citizen. Interestingly, it was the language of architecture that allowed me to define a common ground of understanding of this (and other) cultures that became a foundation for my continued interest in vernacular built environments.

What projects are you working on post-UArizona? Or another way to ask that: What’s next for R. Brooks Jeffery?

Upon retirement, I made a personal commitment not to commit to doing anything for the first six months and focus on spending time with my family, overseeing some house projects and just putzing around, physically and intellectually. However, after a couple of decades of being an administrator, I am looking forward to dedicating quality time to my scholarship and returning to my advocacy of historic built environments, as well serving the Southern Arizona community wherever my skills and experience might be impactful.

View R. Brooks Jeffery's faculty page or learn more about how you can support CAPLA faculty and research.